As fate would have it, the call from one of my doctors at Stanford set off a chain of events that typify my life.

Ms. Corley, came the gracious, slightly lilting accent of the handsome, extraordinarily talented Jaime Lopez, M.D. Are you still in Missouri, or are you in California already? I listened for a few moments, replied, and murmured my assent to his request to change my 9:00 a.m. Friday appointment to Thursday afternoon. Any time, said Dr. Lopez. Three, four, five, it doesn’t matter, I will be there when you arrive. Just call this number, it’s my personal cell phone.

I left Montara then, making my way east to the Delta Bay. Along the way, I stopped and bought dates at the market just as I turned from one highway to the last leg of the journey. Then I drove along Brannan Island Road, and thus into the heart of the Delta, where the San Juaquin gets lazy, and the boats drift, and the people lift their hand from the steering wheel as you pass.

Later, I slipped back down the interstate and crossed into Palo Alto from the South Bay bridge. My breath never left my body for the entire trip, as the sun rippled on the waves and the tiny birds skimmed across the surface. I pulled into the parking lot at 4:30, texted Dr. Lopez, and then entered the building just as the evening staff came on duty.

We talked for quite a while, Dr. Lopez and I. He explained about the conference at which he had agreed to speak, thinking it was Saturday. We talked about his lecture, on the allocation of resources for neuro-diagnostic services. He explained his theory of putting aside a strict cost-benefit analysis favored by the administrators, and focusing on quality, patient perception, and result.

Then he applied the deadly toxin to my spastic legs, deep into the muscle, talking all the while in his melodic Mexican voice. Later he would tell me how astonishing he found his life. He came to America legally, with his parents at age four. He said, I tell my colleagues, I will not starve. I can do a little work for free. I asked if he had grown up in poverty. He smiled, leaned against the elevator door, and nodded. Unbelievably poor, and look at me now. This is why I do things for people in need, because of the bounty which is my life.

The elevator doors closed on the brilliant flash of his smile and the warm brown glint of his eyes.

That night, as I curled to sleep in the little bed in the tiny house which I had secured online for the one night in Palo Alto, I thought about his good fortune, and mine for finding him and the other doctors who have helped me. A surge of humility overcame me and kissed my dreams as I slept.

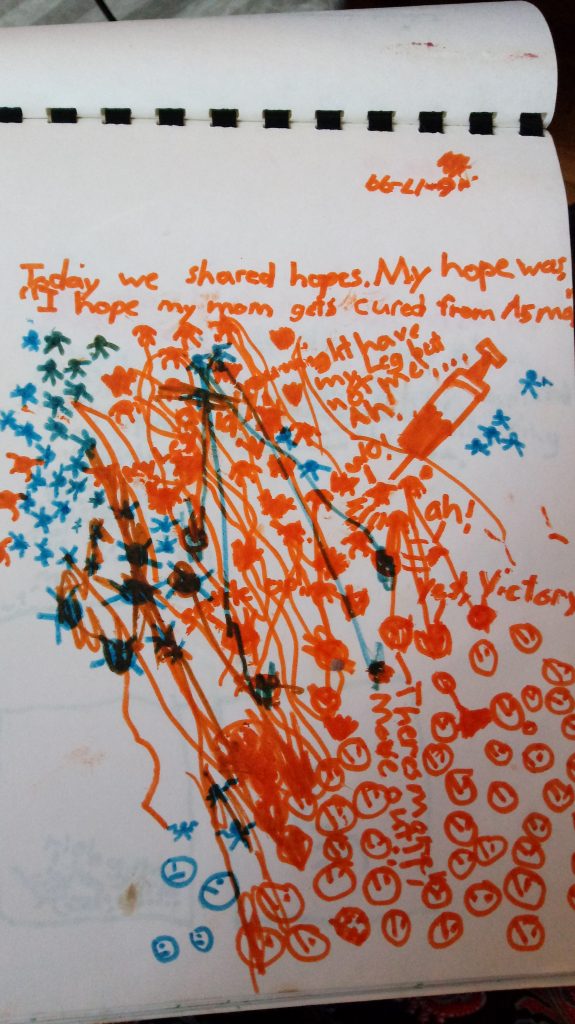

In the morning, I went over e-mail and realized that a flood of messages had fallen into my inbox on the wake of a couple of telephone calls on one of my sticky-wicket guardian ad litem cases. And so, because I had accommodated Dr. Lopez’s request to reschedule, I had three or four hours to devote to helping a ten-year-old girl and her six-year-old brother; and perhaps to set in motion changes which might relieve them of extraordinary anxiety.

As I wrote, I heard two men describing a program which they had started to teach yoga and mindfulness in the local schools. Having just told my ten-year-old client to try yoga before bedtime as a way of easing into sleep, I found their conversation irresistible. I shamelessly eavesdropped, then rose and gave them my card. I introduced myself, took their names, and explained the appeal to me of their mission.

Then, suddenly, I had no further reason to tarry. I made Half Moon Bay by noon. Thus did I find myself in The Posh Moon, where a lovely woman in a navy blue hat sold me a sweet little present for my secretary Miranda’s five-year-old daughter, Aubrielle. The same woman had tucked a little medallion of an angel into my hand when I complimented her hat. She had no idea what angels mean to me. I cried. I admit it: I stood at the counter and cried, having no shame, and certainly no concern for who might see.

Out on the sidewalk, I ran into Kristin Hewett, an artist whom I see year in and year out. But she no longer has her shop and had moved to Oregon, so it made no sense that I could walk down the stretch of broken concrete in front of her old store just as she exited, having come to town to consign a few of her jewelry pieces and chat with the new owner. No earthly reason brought me to that exact spot at the perfect time, except the chain of events which began the prior day with that call from Dr. Lopez.

We hugged one another, caught up on our respective lives, and exchanged phone numbers. Then she hobbled on one bad knee, a cane, and a shaky leg up the three stairs into Silk and Stone. She showed me the pieces of her design, and later, after she had left, I bought one for Miranda, who deserves all the gifts I can afford.

And then, at last, when lunch had been eaten and presents stowed in my suitcase, I made my way just a bit further east, to the Cabrillo Highway, and twenty miles south. At three o’clock, I arrived at the place where my grand and glorious love affair with the sea began: Pigeon Point.

I’ve eaten dinner now. The other guests chattered at the table or took their bowls of rice and pasta to the picnic benches outside. I sat over my potatoes and mushrooms, smiling, silent. I gave one of them my oil to use, and offered corn tortillas. I scooted further down so a young couple could sit adjacent to one another. Outside of the kitchen window, the sun began to set, and I breathed — long, deep, and satisfying, that breath, like no other I have taken in the awkward weeks since my last visit here.

Night falls. The gulls call to one another across the water, noting the dying light to the west. Here in Dolphin, I sit alone at the table. It always comes to this: The setting sun, and the cry of the birds, and me, alone with my words. My peace. My joy. Here, at the edge of the world, as evening draws to its gentle close.

It’s the fifteenth day of the forty-fifth month of My Year Without Complaining. Life continues.