Paula said, “What are you feeling?” and I looked at her with more unease than I expected.

“Like I want to throw something through a window,” I replied. My standard answer in times of anxiety. “Like I’m late for something. Like my belly wants out of my dress.”

Paula smiled and eased down into the rocker from which I kept leaping to pace around the room. “That’s labor, my dear,” she told me, smiling, from her vantage point of a half-dozen homebirths of her own.

Labor. Two full days before my scheduled C-section at 34 weeks gestation in what had, for the past three months, been a fairly smooth center after a horrible start.

I had known of my pregnancy since Thanksgiving. But in late February, I bled for hours and the doctor told me that I had miscarried. On examination, she confirmed the loss of a fetus but amazed me by saying one remained. “You clearly were pregnant with twins,” she advised me. “Hold onto your hats, we’re still in business.”

The medical profession uses insulting names for female body functions, and this case proved no different. Cervical incompetence forced me to stop traveling by mid-April after a scare on a Cessna 206 coming back from a foreclosure hearing in Natchitoches, Louisiana. I felt the weirdness halfway through the six-hour hearing. I twisted the fake wedding ring which I wore and put my hand in the small of my back to balance myself and ease the pain.

“Mrs. Corley, do you need anything?” The judge looked concerned when I admitted that I might need a bit of help. He called in an extra bailiff to carry my exhibits. On the way out the door, the Federal Land Bank officer turned to his lawyer and snapped, “I can’t believe you got beaten by a pregnant crippled girl from Arkansas.”

I didn’t stop to tell him that I only lived and worked in Arkansas. I’m from the Show-Me State! I hurried out of the courthouse and told our pilot, “I’m not excited about having this baby in Arkansas; I’m damn sure not having it in Louisiana!”

We flew back to Springdale with a storm on our heels. He radioed his full-time boss, Sam Walton’s daughter, and said, “I’ve got one of the Arens & Alexander lawyers in my plane and she’s in labor.” They sent a private ambulance for me.

Cervical incompetence. The damnedest part of the constant premature labor involved its impact on my spastic legs and my right hip with its car-accident damage. Every time a contraction rippled through me, my legs would seize and my hip would pop from its joint.

They stopped the labor in April and sent me to bed. The firm for which I worked moved my office to the little apartment which I rented when my house in Windsor got too much for me to handle and the doctor worried about me being so far from Fayetteville. My secretary Laura and her husband Ron, my law clerk, set up shop in my living room. A round-robin of phone-tree friends checked on me after hours.

Paula’s turn came that weekend, the last weekend before my son was scheduled to be brought to the world by the Irish midwife and the local OB-Gyn. So there we were, in my apartment, me walking back and forth and Paula on the phone with the doctor, holding a watch with a second hand. A grin broke across her face and she said, calmly, sweetly, “I think we better go.”

I labored until midnight. Unproductive, they pronounced — yet another word that made me feel inadequate, as though I had failed in the one task that nature intended me to perform at my best. So I went home after breakfast on Sunday, and on Monday the crew packed me in Ron’s car and we caravanned back to the Washington Regional Medical Center for the real show. A bad dress rehearsal portends well, we supposed.

With Laura at my side, and Ron just beyond the swinging doors along with eight or ten folks from the law firm, I let them strap me to the table, cover my hair, and wheel me under the lights. Then we waited, for the doctor’s basement drain had failed and she got delayed by the Roto-Rooter guy. When she finally arrived, we all listened to the entire story as she scrubbed.

At 1:50 p.m. on 08 July 1991, an absolutely breathtakingly beautiful baby boy emerged from an open wound in my body. The midwife Moira held him above the drape. As she encouraged him to breathe, he smiled and then I heard his first sound: Laughter.

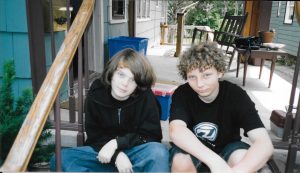

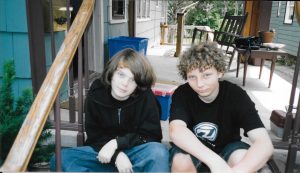

In the thirty years since that astonishing, amazing experience, Patrick Charles Corley has never failed to bring joy to his mother. For my part, I have made some shockingly poor choices in trying to execute my parental obligations. Time and time again I ruefully echoed the famous line from A Thousand Clowns, uttered by the main character about the nephew of whom he seeks custody: “My only hope is that he speaks well of me in therapy one day.”

A village raised my son. His substitute mothers, Katrina Taggart and Mona Chebaro, gave him glimpses of a type of family life that I could never hope to create. They loved him as well or better than any blood relative, as did his beloved aunt Penny Thieme, she of the all-night movie sessions and art lessons. My sister Joyce made sure that he had all the fun stuff, like Barney and Batman sheets and pajamas, bug boxes, and birthday cards in the mail. Every adult in my life became a linchpin in the castle that I tried to build for my son, including “Uncle Alan” White who brought humor, compassion, and empathy which I somehow could not quite convey.

Patrick has his own life, in Chicago. He works as a union organizer. A gifted writer, he also taught himself to create computer graphics and hosted a YouTube channel until his community work crowded out that particular endeavor. On it, he explored “architecture & urban spaces from an anti-capitalist perspective”. You cannot imagine how proud his extraordinarily thoughtful efforts made me. And not even proud: In awe. I have no standing to feel pride, because what my son has become resulted from his own determination to apply his talent to the betterment of a world which he finds lacking but still worth saving.

On that day in July 1991 when I knew that my first — and only — child would be making his entrance into that world within a couple of days, I did not foresee the years of wonder and growth which awaited me. I did not have the sense to fear that I would not be an adequate mother, though that fear would often grip me throughout his childhood. I just wanted him to be there, to come out right now. I longed to feast my eyes on the face which I had been imagining as I watched the alarming growth of my body over the weeks during which I served as the vessel for his incubation.

Most people raised their eyebrows when I disclosed that at 35, I intended to give birth to a child on my own. One person suggested that I give my baby “to a real family”. Another said, “Your life will be very difficult,” to which I replied, “Well the first three decades were sheer hell, so that will be an improvement!” She shook her head. “You’ll see,” she warned.

I did see. It was difficult. Very difficult, even. I missed my mother. I regretted not moving to St. Louis to be closer to my family of birth. I tried marriage, hoping that a stepfather would give my son what I could not. I despaired so many times: when that marriage failed; when I had no answers for the angst of my teenage son; when my medical issues took me to the hospital time and time again during his elementary school years.

What with one thing and another, like his busy life, his independence, and the pandemic, I have not seen my son since September of 2019. I will not see him until September of 2021. I tried to curate a special set of gifts for his thirtieth birthday — gifts which recognized the importance of three generations — mine, his, and the one before me whose members he never got to meet. As with everything that I have done as a parent, I cast those choices out onto the sea with no expectation of return. I do not know if anything that I have ever given my son means even a tenth of everything that I have gotten from him — the education he provides about politics and human interaction; his wisdom; his sense of justice and equity. I learn so much from him. I have grown so much listening to his ideas, his articulation of his own compassionate views, and his critique of what he sees through his extraordinarily perceptive eyes.

I can’t pretend to know whether the material goods which I sent to Patrick adequately convey my love and admiration. I can only pray that as he closes out his third decade, he takes with him some sense of how loved he is, how treasured he is, and how worthy he is. I do not know if I was enough for him, but I can absolutely say, without hesitation, that he is more than enough for me.

It’s the eve of the eighth day of the ninety-first month of My Year Without Complaining. Life continues.

-

-

Patrick Corley & Chris Taggart

-

-

Patrick Corley & Maher Sagrillo

-

-

Patrick in a play at DPU, I believe

-

-

My son and myself at the VALA Gallery in Kansas City, c. 2014.

-

-

My son in the California Delta

-

-

In Chicago.

-

-

Photo courtesy of Penny Thieme.

-

-

Our last photo at the Holmes house.

-

-

Christmas 2017 at Angel’s Haven.

-

-

Patrick, my cousin Paul Orso, and me.