I first ran away from home in December of 1976, if you don’t count the time I fell asleep in a laundry hamper and my parents had to call in the Boy Scouts to search for me. I stumbled upstairs hours after the groups of tired teens had returned and stood in a huddle around the small frame of my anxious mother. Stunned, confused, and probably damp from hours without a bathroom, my five-year-old self emerged from the hallways rubbing my eyes. I didn’t understand the gasps or my mother’s hurried, tight embrace.

Sixteen years later, I stashed my boxes of books and my folding rocker in my parents’ basement and took an early plane to Boston just before a storm dumped twelve inches of snow on the still and shuttered town. I had secured early graduation by dint of changing my major to anything in which I had enough hours to forego the last semester. Besieged by the aftermath of three years of poor decisions and hard-drinking, I thought a change of venue might be in order.

But I was wrong. Instead of preparing for graduate school at Boston College, I started bar-hopping with a theatre crowd. Working a desk job during the day allowed me to keep pace with their spending, but I would never hold my own with their wine-consumption or the passive way they traded partners. By September, I faced the stark reality that I had to crawl back to St. Louis or surrender to the menacing clouds hovering thick around me. My mother sent my oldest brother in her car to fetch me back.

For a while, then, the Jennings household consisted of my mother, my father, myself, and my youngest brother Steve. If I close my eyes and concentrate, I can almost imagine that I remember much about the next five months. I got a job, certainly; and I tried to reconnect with the college friends who had all started their professional lives. I resurrected my local grad school applications. And I drank. Hard; which might account for the haziness of my memory of that time.

One morning I came out from the back of the house where I evidently had been sleeping. I entered the kitchen as my brother stood with his hands braced against the counter. His hair fell across his eyes. Stubble dotted his chin. A cigarette dangled from his mouth. He kept his eyes fixed on the coffee maker, from which the usual promising sounds could be heard.

I started to laugh. My little brother, clearly hung over, mesmerized by the gurgle of the percolator! A few decades later, I wouldn’t find the thought amusing; but back then it all still seemed so much like one’s normal life.

He switched his stare to me and my laughter died. Silence surrounded us for a long moment. Then he shook his head. You don’t look much better, Mare bear, he said, in the softest, saddest voice.

Over the next twenty years, I would lose touch with my brother Steve. He got married and divorced, twice; he cared for our dying mother; he earned his nursing degree; he quarreled with our father, when the failed first marriage sent him back home for a time. I traveled a similar path, and my road took me out of St. Louis to which I would never again return except for holidays, and weddings, and funerals.

My mother’s death came first, in August of 1985, quickly followed by her father’s passing that December. I brought my new baby home to bury my father in the fall of 1991. And in June of 1997, we stood in a small, sad circle around the brass box which held the cremated remains of my little brother Stephen Patrick Corley. Though the exact date when he died by his own hand remains unknown, I believe his death certificate sets it at twenty-five years ago today, 14 June 1997.

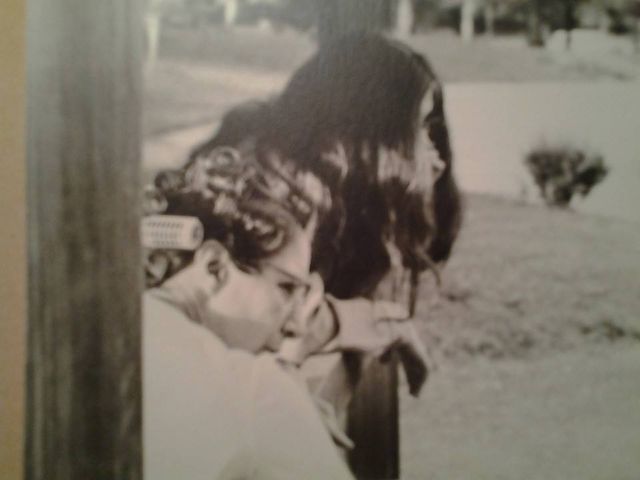

Of all the difficult tasks which I have faced in sixty-six years, telling my son that his favorite uncle had died might stand fairly close to the top of the list. My five-year-old quietly asked, You mean Uncle Steve like black-shirt Uncle Steve? I choked back tears and nodded. Black-shirt Uncle Steve like Uncle Steve who gave me the alien-catcher? I sobbed, and whispered, Yes.

My son reached his little arms around my neck and pressed his face against mine. I crouched down and wrapped myself around his body. I had no other words. I had nothing to offer my boy to comfort him as I collapsed within my own grief. I could only hold him, and be held by him, and pray that whatever essential element of my lost sibling remained on this earth would entwine itself around both of us.

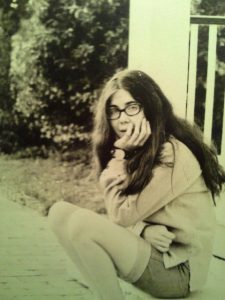

I named my son after my little brother because I could not think of a better man for him to emulate. I understood the dark side of Steve’s existence; and I prayed that in giving his middle name to my son, I didn’t doom my child to the loneliness which must have driven my brother. For my part, I remember his dancing, the jaunty stroll with which he entered any room, and the strength of his profile. I hear his voice; I see his face; I cling to a gossamer thread which links his soul to mine. Every day we spent together; every holiday in which we scampered across the lawn as children; even the grim hours when he tried to explain the demons on his back — I hold them all in my heart.

Like the sight of his hunched form in my mother’s kitchen, those memories of my brother’s life shuffled themselves into some treasure box within my mind. On days like this, I take them out one by one, and study the images of my brother’s smile. I strain to find traces of the pain which drove him to his end. Brother, oh my brother! How I miss you! But then, I imagine him sitting on the banks of a river, with a willow tree rising high to shade him, and a song bird singing in the distance as he sleeps. Fare thee well, Stevie Pat; fare thee well. I love you more than words can tell.

It’s the fourteenth day of the one-hundredth and second month of My Year Without Complaining. Life continues.

Brokedown Palace, by the Grateful Dead

My Patrick and his Uncle Steve.

Away

By: James Whitcomb Riley

I cannot say, and I will not say

That he is dead- . He is just away!

With a cheery smile, and a wave of the hand

He has wandered into an unknown land,

And left us dreaming how very fair

It needs must be, since he lingers there.

And you- O you, who the wildest yearn

For the old-time step and the glad return- ,

Think of him faring on, as dear

In the love of There as the love of Here;

And loyal still, as he gave the blows

Of his warrior-strength to his country’s foes- .

Mild and gentle, as he was brave- ,

When the sweetest love of his life he gave

To simple things- : Where the violets grew

Blue as the eyes they were likened to,

The touches of his hands have strayed

As reverently as his lips have prayed:

When the little brown thrush that harshly chirred

Was dear to him as the mocking-bird;

And he pitied as much as a man in pain

A writhing honey-bee wet with rain- .

Think of him still as the same, I say:

He is not dead- he is just away!