My baby brother Stephen disappeared from this difficult world some time between June 07th and June 13th in 1997. His gravestone notes his date of death as June 14th, but they could not say with any certainty. They gave the span within a week.

We buried him in the Corley family plot in a cemetery in St. Louis, with the mother whom he loved beyond all measure, and the father whom he equally loathed. His cremains bore a Grateful Dead sticker. Someone tossed Cardinals football tickets into the small hole dug for the brass box. His ex-wife stood stoically at my side, eyes blank, hands clenched. She had mourned the loss of him years before that day, and doubtless has never stopped.

This morning I saw a little news report about Pat Sajack retiring from the television program Wheel of Fortune. My heart skipped, and just for a few minutes, I sat by my mother’s bedside on some evening in 1985 when I had driven to St. Louis to take a stint in her sickroom. Vanna White stood by the letters and Pat gestured for a contestant’s guess. As the letters flipped, my mother chuckled and held the telephone receiver. Inevitably it rang, she listened, nodded, and pronounced the caller to be correct. When the next ring sounded, she lifted the receiver and chortled, Too late! Thus did we play a cross-country game with our dying mother, with the first person to guess the Wheel of Fortune answer winning the priceless prize of her praise.

On one of those visits, my brother Stephen and I stood in the kitchen talking over coffee. He shook his head and said, with his paramedic’s bluntness, It won’t be long now. He did what he could. Whatever else you might say about my brother’s behavior in the last few months of our mother’s life, he did love her. He taught me how to melt her pain pills in the microwave, a skill that I stubbornly refused to understand how he learned. He showed me the easiest way to stroke her throat to get her to instinctively swallow. He sat in a chair by her side on many nights, doing what he could for her. He took her pain into his heart. We all did, really; but her baby seem to feel it quite keenly.

A decade later, he still grieved. He had a lot of monkeys on his back, did my little brother; and his inability to save his mama nestled boldly and cruelly among them.

I try to recall his face, and hers. I start the annual grieving time right about now. I imagine that last desperate drive he took, to his country land. I won’t let myself picture the rest of it, except that quiet spot beside a tree where his friend later found him.

I had a mural painted on my house several years ago in his honor. The harsh sun had faded its bright colors, but I’m having it restored. I think of my little brother sitting beneath a willow tree on the banks of a river, as the sun eases itself downward in the western sky. He would be happy there; or if not happy, at least, perhaps, at peace.

It’s the seventh day of the one-hundred and twenty-seventh month of My Year Without Complaining. Life continues.

June Night

How can I sleep while all around

Floats rainy fragrance and the far

Deep voice of the ocean that talks to the ground?

Oh Earth, you gave me all I have,

I love you, I love you,—oh what have I

That I can give you in return—

Except my body after I die?

- My mural commissioned in memory of Steve’s favorite Dead song, “Brokedown Palace”.

- The Corley Headstone

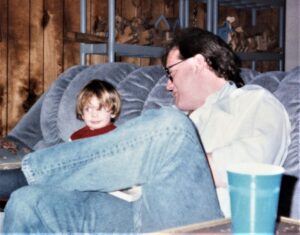

- Patrick Charles Corley (left) and Stephen Patrick Corley on one of my brother’s last Christmases among us.

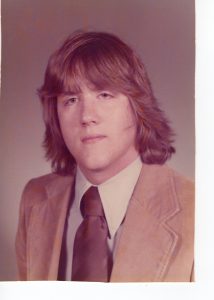

- Stephen Patrick Mark Corley

It’s the seventh day of the one-hundred and twenty-seventh month of My Year Without Complaining….

It reads like a heavy June evening, humidity rising, not a breeze to be found, daylight nearly done, all the night bugs and creatures beginning to stir…