This post began as many do, with sentences clumsily rumbling around in a head full of lather. I got stuck on the first clause. The internal debate distracted me so that I rubbed conditioner into suds. I had to restart the process of washing my hair and lost the writing momentum.

But what I wanted to say lingered. Fair warning: If you came for the cookies, you’ll want to pass on the Paregoric. I’m not offering poignancy today, nor sweetness, nor anecdotes the message of which you can ignore, lost in the melody of the narrative.

In 1973, I sat on the stage of the parish hall at Corpus Christi in Jennings, Missouri, and listened to the class goals and class predictions. On the limited occasions when I’ve recounted this event to my intimate friends, I’ve pretended not to remember who read these yearnings and prognostications, but I do. I won’t credit her — or blame her, either one. I’ll let her hide in the lie of forgetfulness, shrouded by time, safe from your scrutiny. I’ll pretend that she would not care, or would not remember. In fact,I’ll assume that she no longer attaches any importance to a brief event which has festered in my belly for forty-five years.

We had the unique position of being the last graduating seniors of our high school, not counting a few sneaky girls from what would have been the class of 1974 who walked with us. Because of the staggeringly sentimental significance of being the last class to receive our diplomas from the school, everything we did carried a rich overtone of hidden meaning. Thus the nuns admonished us to carefully craft whatever would appear in the baccalaureate program or the yearbook.

They didn’t need to worry about me. My stated goal had been the same for a decade: To have a poem published in The New Yorker. In my best cursive, I added this dream to the list of accomplishments under my name. I pushed aside the trepidation which rose in my stomach whenever I opened myself to ridicule.

But none came; at least, until the baccalaureate breakfast, when the girl who shall remain unnamed read our class predictions. Mine? “Ten years from now, Mary Corinne Corley is still signing her name, Mary Corinne Corley”.

At seventeen, I had felt the stain of shame more times than I could even then recall. On so many other occasions, public humiliation followed me. At five, when my father staggered out half-dressed, drunk, and stinking with the little neighbor kids staring from the sidewalk. Walking the streets as a six-year old, huddled in my coat under a starless sky, singing church songs and waiting for my father to pass out back at the house — and pretending not to notice when the lady across the street peered from her curtained windows. At nine, when I listened to my mother explain to the eye doctor that we could not afford glasses. Weeks later, when I appeared at school after Christmas break wearing an ugly pair for which my father’s mother had paid, and first suffered the taunt of “four eyes”. On a hot Sunday walking home from church with a gaggle of boys imitating my awkward gait from a half-block away, behind the back of my unsuspecting mother. When I experienced my first menstrual period, which I didn’t understand, spreading in a crimson flow on the back of my uniform skirt during sophomore English class. The time I got stuck in a stall in the second floor girls’ bathroom, listening to a couple of classmates talk about how disgusting they found me. When I attended the Father / Daughter dance alone, as the school photographer, because I did not trust my dad not to fall down drunk and vomit on himself in the gymnasium.

So what of a girl taunting me by predicting that I would not be married ten years hence, the intended implication of that prediction of how I would sign my name? Of course, I did not doubt the accuracy of her prescience. My own mother had told me to go to college because no man would likely marry me.

I never got a poem published in The New Yorker. I got three published in Eads Bridge, and then got distracted by Scotch and sex, the latter of which I mistook for love too many times to count. When I did marry, I did not change my name, a fact which various people praised or lamented, depending on their opinion of me, of equality, and of the man whose name I chose not to assume. I stopped writing poetry with any regularity in 1978, when a musician told me that my poems didn’t even rise to the level of good home-grown stuff and should be relegated to the box of drivel that I would eventually burn. Or words to that effect.

When I started this blog, my sole intention was to force myself to go 365 days without voicing one complaint. I truly felt that if I could do that, stars would align and everything that I wanted for myself would unfold before me. My marriage would be saved, the pain in my legs would go away, I’d forget the terrible tragedy of my childhood.

None of that has come to pass. This blog gradually morphed into something much more than an arrogant litany of my virtuous silence in the face of the stupidity of others. As it evolved, so did I. My marriage failed regardless; the pain in my legs, unmedicated after forty-five years of being numbed by narcotics, rose to claim me; and the immutable reality of the neuro-biological impact of family violence forced me to accept that I will never be the person that I might have been.

It turns out that my offering to the universe of 365 days without complaining failed, but not because I failed. The bargain existed in a plane of pretense. I could not make life fair or even different by silence in the face of difficulty. I could only make my life better one day at a time through effort, and awareness, and being open to the flickering candles which cast their cheerful light into my personal gloom.

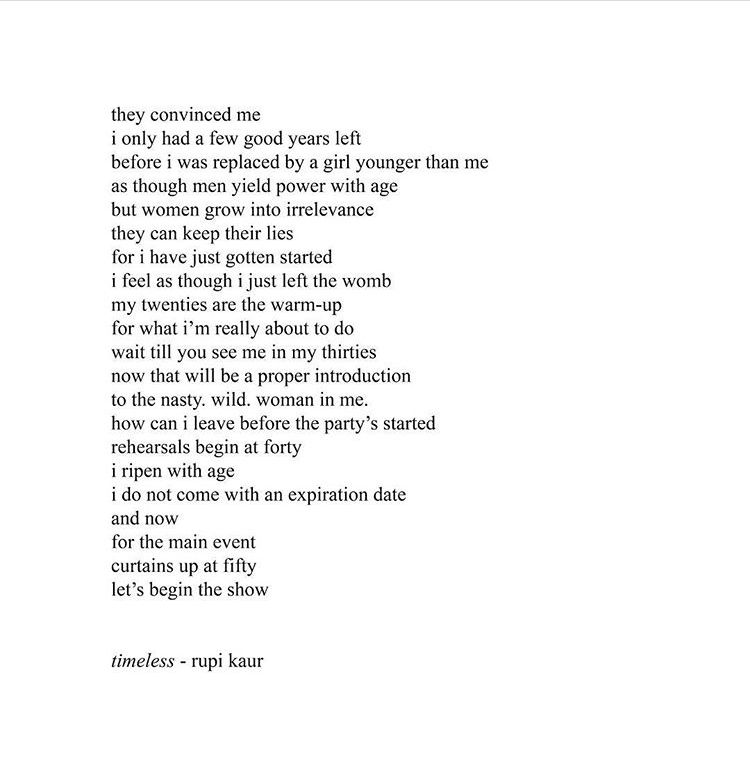

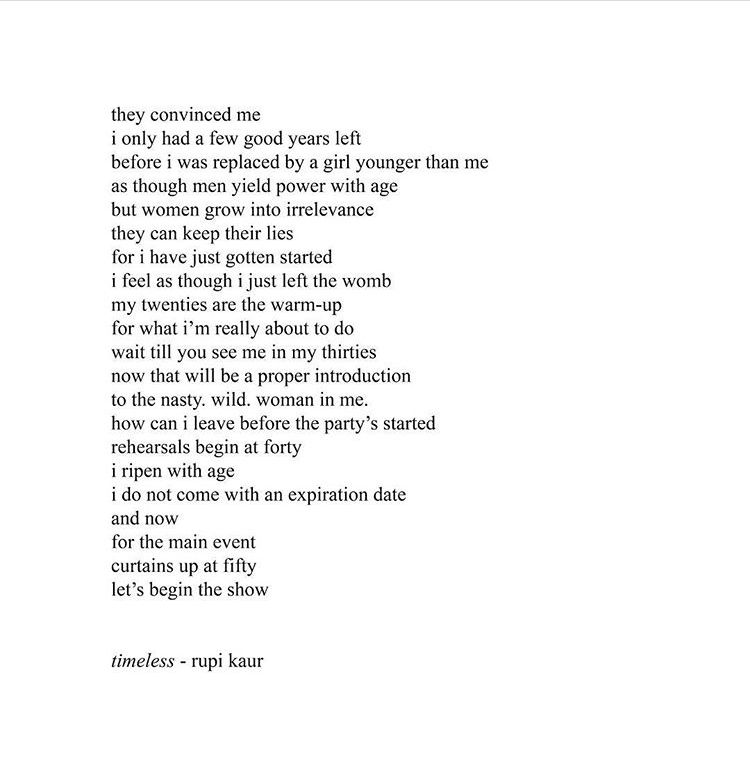

During the last few weeks of my Kansas City days, a girl at one of my favorite juice places told me about Rupi Kaur. Since then, I’ve used many of her poems to illustrate passages here. She’s taken a place beside Sara Teasdale in my heart. Both of them speak to whatever inside me yearned to write poetry despite my obvious inability. Rupi Kaur has the same sort of eternal voice of her generation that I perceive in Sara Teasdale.

I don’t know if Rupi Kaur ever yearned to publish a poem in a particular periodical, as I did, back in my high school days. When I look at her photographs, I see a woman with impeccable teeth, lovely olive skin, a sheath of extraordinary black hair, and a petite body encased in sophisticated clothing. I see the attributes the lack of which I always presume inhibited my success. I don’t envy her, but neither am I at all surprised that fate apparently has dealt her the hand which I craved. Somehow, I expect the pretty girls to succeed. I, too, learned the truth at seventeen.

Yet here I sit, in my writing loft in a tiny house on wheels in the California Delta. I eventually got the conditioner washed out of my hair, and sprayed rose water on the fine lines which snake across my face. I rubbed cream from the dollar store onto my tortured feet, struggled to encase those feet in soft socks, and slid them into the high tops that I bought to stabilize my ankles. I slid my mother-in-law’s sapphire onto my left ring-finger, tugged on flowered tights, and pulled a Lady Liberty t-shirt over my head. I slugged down the last of the re-warmed coffee and poured my first little glass of cold water for the day. I climbed the stairs, pushed open the window, and settled onto the wooden chair in which I have sat to write nearly all of the fifteen-hundred or so entries that I’ve amassed on this journey to joy. I raised my hands, and started typing. Yet again. No complaints. Full speed ahead.

It’s the twenty-sixth day of the fifty-fourth month in My Year Without Complaining. Life continues.

“Timeless”, by Rupi Kaur

RUPI KAUR READS ‘TIMELESS’

The unvarnished truth: Yours truly, the real Missouri Mugwump, 26 June 2018.