Every year on August 21st I awaken before daybreak. I listen to the sounds of the settling room and remember another room, thirty-six years ago. My cousin Theresa Orso Smythe gave me safe harbor for a few hours so that others could take my place beside my dying mother. As I lay on Theresa’s couch in the grey light of dawn, the phone rang. My sister Adrienne’s voice said, “It’s time to come home.”

At my mother’s funeral, my cousin Theresa sang “Goin’ Home” a capella and so beautifully that I swear my heart stopped. No other sound invaded the church as the strains of the poignant spiritual faded. My mother loved that song and the symphony on which its melody was based. In her last weeks, she begged us to let her go home. Speaking for myself, I resisted her pleas. At twenty-nine, I could not imagine the rest of my life without her.

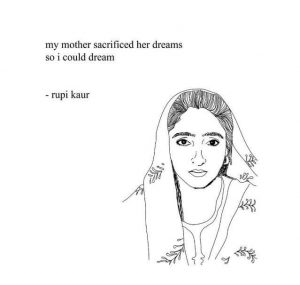

Yet she left us; and everything that I have experienced since then has been in the context of being a motherless daughter. I remember walking with her in the backyard so many times in the early days of her illness. I brought her stool out to the garden so she could sit and dig weeds. I stood by, helpless, not knowing whether to bend to assist or let her have the joy of it without my interference. She tied a scarf over a head made bald from chemotherapy and wrapped her frail body in heavy sweaters. We sat on the park bench by her grape vine. She asked me about my life across the state in Kansas City. Mostly I told pretty lies. I don’t think I fooled her. But I could not bring myself to taint her days with the truth of her youngest girl’s ineptness at living when she herself had worked so hard to make a life which now would end far too soon.

Looking back on the sweltering August of 1985, I mostly recall drinking too much Scotch and driving to St. Louis every weekend to take a turn sitting with my mother while she slowly left us. On the Friday before her Wednesday death, someone in the hospice group suggested that we might consider gathering the siblings and anyone else who wanted to see my mother before she passed. I called opposing counsel to get a continuance in the trial scheduled for Monday but he would not agree. Desperate, I reached out to someone whom I knew had the judge’s home phone number. Arrangements made, I fled.

Losing a mother at not-quite-thirty pales in comparison with the same experience at three or thirteen. I realize that I’ve been incredibly lucky in many respects. Nonetheless, I often wonder if I would have made different choices along the way with my mother’s voice in my ear other than as a memory. I could not truly predict her counsel. I could only imagine that she spoke to me. Her words did not necessarily reflect anything except my own yearning.

Some of my siblings feel this loss as keenly now as we did three decades ago. Some of them seem to have risen above the pain. Some seem to have a balanced life, despite what we have experienced or perhaps because of it. I move through most days without reflecting on the past; but on these anniversaries, what was and what might have been seem to come together in a loud crescendo of longing.

I had my breakfast early. I made strong coffee and sat at my table, contemplating the gift of yet another day. I posted my mother’s picture on social media. My sister called and we talked of everything else — my week and hers; the debacle in Afghan; the relative kindness and cruelty of children. After the call, she sent me a text making note of the day and telling me that she loved me. I replied that I loved her too.

I’m struggling to understand a general sense of immobility which has haunted me for many years. In my favorite book from childhood, Emmy Lou, (fn) the aunts and uncle who are together raising the main character have a long conversation about Emmy Lou’s progress in school. She does not seem to be catching up, one aunt mournfully observes. Nor on, the uncle sadly replies. My mother gave this book to me. I think she saw me in that little girl, who struggles to matriculate through an often confusing life. I quite understand her befuddlement.

The morning has waned. I have chores to complete which, truth be told, I have been avoiding all week. My lethargy jeopardizes my planned productivity. Despite being out of bed for five hours, I’ve not yet showered or dressed. Any moment, I shall spring into action. I shall channel my mother. Eventually, when the day bleeds into evening, I will sit on my porch with a cup of tea. In that hour, she will come to me; and my heart will feel so much less forlorn that I might even mistake the sensation for happiness.

It’s the twenty-first day of the ninety-second month of My Year Without Complaining. Life continues.

In Memory: Lucille Johanna Lyons Corley – 10 Sept 1926 – 21 August 1985

- My mother and me, at the Bissell House in Jennings, Missouri, 1970.

- My aunt and my mother

Fn: I take my handle, “Missouri Mugwump”, from an anecdote in this book.