I became a daughter as easily as some people swear, or laugh, or throw accusations against a wall hoping that the mud will stick. My mother said her labor was easiest with me. I entered the world on the day and at the approximate time expected. September 5th, 1955, at five minutes past nine. My father celebrated my 9/5/55 birth with 9-0-5 beer from the store down the street from our house.

My mother settled a modest amount of expectations on me as I grew. She did not expect me to walk after my illness. I surprised her by struggling to my feet and toddling around on tender legs. After that astonishing feat, my mother tentatively encouraged finer skills. I read at three and a half. I learned to make potato pancakes at five or six, standing on a stool in the kitchen. I took a job babysitting a family of seven or eight kids when I started high school. I enrolled in an AP History class. My mother assumed that I had a good foundation for modest success.

Her dreams for me stopped at greater goals. She did not think that I would ever marry. She discouraged me from taking dance class. She gently steered me from strenuous activity like sports or hiking. She wanted me to push myself, but with reasonable restraint. She trusted me, but knew my limitations.

During my mother’s last months, she made a teddy bear for me to give a future grandchild. She used leftover purple flowered cotton from one of her scores of wrap-around skirts sewn from the same pattern year after year. She gave him a little turned-up nose and cross-stitched eyes. She chose purple so it could work for either gender.

I was two weeks shy of my thirtieth birthday on the day my mother died. I cried myself to sleep for months with that teddy bear clutched in my shaking arms.

Becoming a mother turned out to be a lot more difficult. My son Patrick’s birth followed several miscarriages, each more frustrating and painful than the last. But his actual entrance to the world took twenty-seven minutes. A doctor and a midwife performed the surgery, counting stitches, counting instruments, chattering about the doctor’s septic system troubles as they coaxed my son into the sterile surgery theatre. He entered laughing.

I made a lot of poor decisions during my son’s childhood. I daresay he had to overcome my weaknesses and the foolish choices that seemed reasonable at the time. I gave him what I could; and tried to include room enough for growth and exploration. I pushed my sorrow beneath the surface; beat back the pesky demons; and invited a village into the fluid parameters of his world.

My mother taught me to sing, and make Austrian pancakes, and iron handkerchiefs. She notched her chin an inch or two higher when adversity crashed against her. She never felt sorry for herself — or if she did, I never saw it. When we walked in her garden a few months after her cancer diagnosis, she told me that an angel had come to her in a dream. “He said I had a year,” she told me. “He said it would be a good year, full of life and the sound of my grandchildren’s laughter. I can live with that,” she concluded, unaware of the irony lacing her statements.

When Patrick was about a year and a half, we lived in an apartment in Kansas City. The door opened to a hallway. Every Sunday, the newspaper guy burst into the building and tramped up and down the stairs, tossing a paper in front of everybody’s entrance. One week, in the dead of winter, the wind howled as the delivery man swooped into the building. Patrick stood by the window in his little romper. He pushed aside the curtain and watched as the van drove away. Then he turned and said, I get the paper Mommy! Your legs don’t work very good!

He stood on his tip-toes to turn the lock. He strained to get the latch undone, and pushed the door a few inches outward. Bending, he hoisted the fat newspaper against his chest, and dragged it into the living room. He got it as far as the edge of the rug before it slipped. As we collected the pages, he kept telling me, over and over, I got it for you, Mommy. Patrick got it for you. He never really stopping getting things for me. He dragged laundry baskets, grocery bags, and suitcases across the floor of our house and down our sidewalk. He climbed stepladders to reach things which I could not, until he surpassed me in height. He never refused any request his mother made of him. Maybe I asked too much. Being an only child must be an awful burden at times.

I was not the best mother, but I have raised a damn fine son. Patrick never met my mother. She died six years before his birth. But I see a glimmer of her strength in him. I see her kindness, and her compassion, and her resilience. He has the Lucille Corley sense of humor, a little wicked but never mean. Most of all, he has her unfailing sense of dedication to those whom he loves.

She would have been as proud of him as I am.

I will not see my son for Mother’s Day. He lives half way across the country. I got a card from him with a sweet message written in his left-handed slope. I put it on the wall next to a picture of my mother. It looks good there.

It’s the ninth day of the seventy-seventh month of My Year Without Complaining. Life continues.

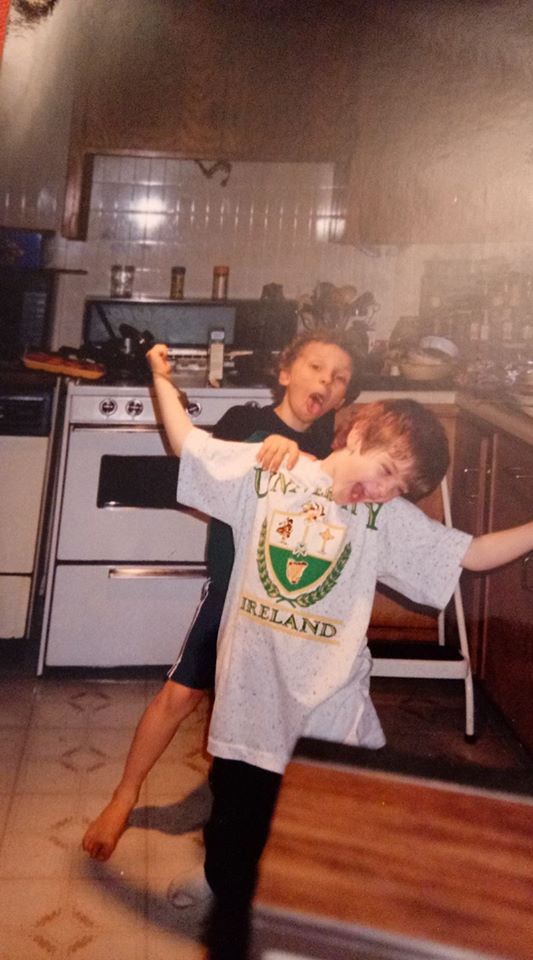

- My son and me

- My son in the California Delta

- Patrick in a play at DPU, I believe

- My mother and me, at the Bissell House in Jennings, Missouri, 1970.

- My aunt and my mother

- Chris Taggart and Patrick Corley